The smallness of "Little Mac"

George Brinton McClellan ranks as the most controversial general of the Civil War. Beloved by the soldiers in the Army of the Potomac, his command of the Union’s premier army during the early years of the conflict generated a storm of criticism and sparked debates still being waged by historians today. McClellan himself was an early participant in these debates, seeking to affix the blame for these failures where he felt it was most deserved – namely on everybody but himself.

In this debate Stephen Sears comes down firmly in the camp of McClellan’s critics. His biography of the general provides a damming assessment of “Little Mac”’s failings, one more starkly illustrated by contrasting them with McClellan’s many gifts. Ranked second in his class at West Point, McClellan was a rising star in the antebellum United States Army before leaving for a lucrative career as a railroad executive. Yet even early on his outsized self-regard generated disputes with his superiors, as he saw what was often reasonable arguments as the product of implacable opponents determined to destroy him.

These tendencies were only magnified by the pressures of war. McClellan’s prewar reputation as a military thinker and early success in the west led to his appointment of the Army of the Potomac at the age of only 35. McClellan set out to build up a formidable fighting force, and Sears acknowledges his strengths here as a military administrator. Yet McClellan’s arrogance and reluctance to commit the army prematurely soon fueled a mounting criticism of his inactivity. McClellan’s own forays into politics (where he won more battles then he ever would as military commander) only exacerbated this, leading to charges that the general secretly harbored Confederate sympathies.

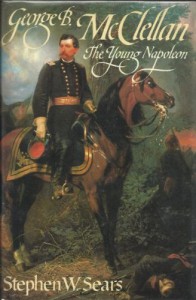

Had McClellan enjoyed success on the battlefield nothing would have come of this. His Peninsula campaign, however, was hobbled by McClellan’s insistence on a deliberate pace and a perennial (and unfounded) fear that he faced an enemy superior in numbers. As a result, despite possessing the most formidable army the nation had ever assembled he was outfoxed and outfought by his Confederate opponents; in this sense the “Young Napoleon” subtitle of this book is ironic rather than accurate. John Pope’s defeat at Second Bull Run gave McClellan a chance at redemption and the famous “Lost Orders” a priceless opportunity to defeat Robert E. Lee, yet Sears’s assessment of McClellan’s failure to take advantage of this is hard to deny. Though Lee withdrew to Virginia after the bloody battle of Antietam, McClellan’s failure to follow up on this success led to his final dismissal as army commander. It was a testament to his stature that he soon emerged as a leading contender for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1864, but the party’s “peace platform” deprived him of what Sears regards as a legitimate chance of defeating Lincoln that year, leaving McClellan to enjoy a prosperous and successful – if anticlimactic – postwar career as a businessman and a politician before his early death at the age of 58.

Drawing heavily on McClellan’s letters and other documents, Sears offers a convincing assessment of McClellan and his military career. As one might expect, the main focus is on his Civil War service, as Sears spends only four of the book’s seventeen chapters on McClellan life before and after the conflict that defined his historical legacy. The portrait that emerges is of a man who, for all of his ability was in the end brought down by his own pettiness as much as his other failings. It makes for a sad tale of a man to whom the nation once looked as their savior, yet who ultimately squandered the goodwill earned by his promise on recriminations over failures that were squarely his own.