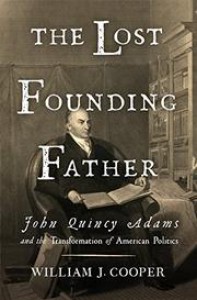

The living link to America's founding generation

It's not unreasonable to ask whether a new biography of John Quincy Adams is needed. In recent years Paul Nagel, Robert Remini, Harlow Giles Unger, Fred Kaplan, and James Traub have all published books that chronicle the life of America's sixth president, which raises the question of what William J. Cooper offers that is different from these other works. His answer is embodied in the book's title, as he sees Adams not as a figure of the antebellum-era politics in which he served but as more reflective of the generation of the "founding fathers" that preceded it. It's an interesting argument, and one that Cooper supports not just by detailing the commonalities between Adams's politics and those of his father's generation, but also by describing Adams's religious beliefs and enthusiasm for intellectual discovery, which are closer to the Enlightenment-era thinking of the Revolutionary generation than the more Romantic ideas that would characterize the 19th century.

The sense of Adams as a man out of step with his times emerges over the course of Cooper’s book. Part of the reason for this was his upbringing, which was itinerant due to his accompanying his father on diplomatic missions during the American Revolution. Traveling through Europe exposed him more directly to Enlightenment ideals, and gave him the motivation to master several different languages. Such an education helps to explain why President Washington selected the 27-year-old Adams as minister to the Netherlands, as he brought to his job a level of knowledge that belied his youth. This was the start of a succession of diplomatic appointments over the next two decades, broken by a term in the United States Senate, and which culminated in eight years as Secretary of State.

Cooper describes Adams’s early career and presidency in a fairly straightforward manner. It is when he gets to Adams’s post-presidential career in the House of Representatives, however, that his narrative hits its stride. This is understandable given Cooper’s background as an historian of the antebellum South, as he brings a different set of insights to Adams’s involvement in the political issues of the 1830s and 1840s than previous biographers. Foremost among them is Adams’s role in the debates over the “gag rule” over slavery in the House during that time, which Adams was at the forefront of the fight against. Cooper’s explanation of Adams’s relationship with the abolitionist movement during this period is a particular strength of this book, as is its role in his development of his nationwide celebrity. As Cooper demonstrates, even Southerners who opposed his championing of antislavery petitioning esteemed the elderly Adams as a living link to their legendary past, which contributed to the national mourning that greeted his death in 1848.

Cooper’s approach makes for a valuable appreciation of Adams’s significance as both a politician and a national symbol. While concentrating on his political career comes at the coverage of his personal life – with his family absent from the text for pages at a time – this seems an accurate reflection of the life Adams lived, in which public service was always at the forefront. It makes for a book that is an excellent resource for anyone seeing to learn about Adams’s long and distinguished public career, as well as what it represented to a growing nation.