Is optimism in science fiction our social coal-mine canary?

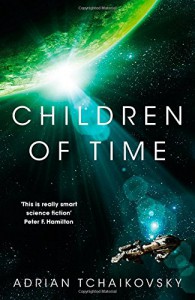

While reading some book-related articles today I came across a description of Adrian Tchaikovsky's 2015 novel Children of Time. Though short, it was intriguing enough to get me to add it to my TBR list, but it also got me thinking about what seems to be the decline of optimism in science fiction.

The trigger was Tchaikovsky's premise about a colony ship that contains the last humans in the universe, traveling to a planet occupied by another species from Earth, this one altered. That very description strikes me as more than a little sad, but also one that I've seen a lot in recent SF in various forms: the representatives of a dying species, struggling to survive. Sometimes it's our fault, sometimes it's just that we've had our run, but what they all share in common is the sense that humanity's last days are behind them.

This matters to me in the sense that for all of their futuristic settings all science fiction is ultimately about the present, which is why I'm worried about what the apparent increase in the prevalence of such tales says about us today. Yes, apocalyptic SF is as old as the genre itself (if you forego the work that gave us the concept as we understand it today, you can find it as far back as Mary Shelley), but it seems to predominate science fiction more today than it did even just a couple of decades previously. Moreover, the more optimistic strain seems to be one the wane, as the novels set in a gee-whiz future of promise and excitement seem fewer and further between than they were in the "golden age" of the 1950s.

What bothers me about this the most is what this says about our times, as it seems that optimism is an indulgence as we dwell more on the negatives in life, on losing what we have than on gaining something more in the future. I could attribute it to living in the eroding white American middle-class, but it's there in a lot of Chinese science fiction as well, which suggests a far broader trend than the one in my own bubble. And what makes it so perplexing to me is that in so many ways life is better for most people than it has ever been. The irony here is rich: in so many ways humanity is actually achieving the promise of a better future, yet we're focused more on decline and catastrophe.

I suspect this is why I've spent the past couple of months indulging myself with old Star Trek novels, as more than ever I miss the idea of an optimistic future — and you can't get much more optimistic of a future than Gene Roddenberry's vision of it. Yet it's suggestive that some of the novels that I've most enjoyed are the ones that spin a darker path out of Roddenberry's day-glo premise. To adapt an old saying, perhaps in the end the fault lies not in us, but in myself.