The Hundred Days, in detail

There are few historical episodes as dramatic as the “Hundred Days” – the label given to Napoleon’s doomed attempt to reclaim the French throne and reestablish his empire. Having driven out the restored Bourbon monarchy of Louis XVIII, Napoleon faced off against the coalition of powers that had exiled him to the Mediterranean island of Elba less than a year before. Though Napoleon struck first and scored some initial victories, his defeat at the battle of Waterloo ended his last bid for power, and led to his imprisonment on the remote island of Saint Helena until his death nearly six years later.

It is an understatement to say that there is no shortage of books on the events of the Hundred Days and the battle of Waterloo, as authors began writing about it almost from the moment the guns stilled and have not let up since. Yet even when weighed against two centuries of accounts of the battle, John Hussey’s book stands out. The first of a two-volume work on the Hundred Days campaign, it is the product of meticulous scholarship and careful reassessment of every significance event and controversy involved. This is evident from the very first chapters, as Hussey looks at Europe’s long history with Napoleon and the events leading up to his decision to escape his exile – a decision born of a mix of boredom, ego, ambition, and frustration with the slights inflicted upon the former emperor by the Allied powers that had defeated him.

With a British officer resident on Elba to supervise him and a British warship patrolling the waters between Elba and France, Bonaparte’s decision was not without risk. His successful arrival in France, followed by his bold journey to Paris, though, defied the odds and achieved his goal. Yet Hussey describes the tenuousness of Napoleon’s hold on power, with many in France still exhausted from his reign and wary of what his return might bring. Aware of the post-exile divisions among the coalition, Napoleon hoped they might provide an opportunity to maintain his throne. Nevertheless, he prepared for war.

And war was coming. Hussey devotes considerable space to describing the coalition facing the returned emperor, with pride of place going to the commands led by Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher and Arthur Wellesley, the duke of Wellington. Hussey spends several chapters dealing their commands, their operations, and their activities, with intelligence operations featured prominently. This is central to his efforts to unpack the events of Napoleon’s 1815 campaign and establish clear chronologies and understandings of what the commanders knew and when they learned it. The issues can often seem trivial, but they serve a clear purpose in serving as the basis for Hussey’s analysis of why decisions were undertaken, and why alternatives were not pursued.

Hussey ends the volume with an account of the battles of Ligny and Quatre Bras on 16 July. Though he details the actions separately, he makes it clear that they need to be regarded as a whole. His explanation is of a piece with the rest of the book, in which Hussey lays out the facts and explains how he reached the conclusions he did. It’s a careful work of often painstaking construction, and is what makes the book such a valuable addition to the already substantial library of works on the events of 1815. Take together with its successor volume, it’s a book that serves as an indispensable history of the battle, one that no serious student of the subject can afford to ignore.

2

2

Eugene Debs and the arc of American socialism

In the first two decades of the twentieth century the Socialist Party appeared to be a growing force in American politics. As Socialist agitators and newspaper editors denounced the evils of the expanding capitalist system, organizers mobilized laborers into unions and Socialist candidates throughout the country won offices at the city, state, and even federal level. Yet by the early 1920s the Socialist Party was in a decline even swifter than their rise, with its membership riven by infighting and marginalized by the increasingly conservative mood of the nation.

No figure better personified the trajectory of the Socialist Party’s fortunes during this era than Eugene Victor Debs. As the party’s five-time nominee for the presidency of the United States, Debs was buoyed by rapidly increasing voter numbers during his first four campaigns for the office. When he ran for the final time in 1920, however, he did so from a federal penitentiary in Atlanta thanks to a wartime conviction for sedition. It was a testament to Debs’s appeal that even while incarcerated he received over 900,000 votes, though as a percentage of the vote is was little more than half of the total he had received in his last bid for the office. No subsequent Socialist party candidate was ever able to improve upon that result, however.

In his biography of Debs, Nick Salvatore makes it clear that a major reason why none of Debs’s successors could duplicate his achievement was because none brought what he did to the party. As a longtime labor leader, Debs possessed an unmatched credibility with working-class Americans, his sacrifices on behalf of whom was part of his appeal. Yet as Salvatore explains, the basis of Debs’s approach to socialism was far more complex than that. The son of French immigrants, Debs left school at an early age to work for one of the local railroad companies. In 1875 he joined the Brotherhood of Local Firemen, and quickly distinguished himself with his tireless activism on the organization’s behalf. It was as a union leader that Debs became nationally famous, as he worked to establish an industrial union in response to the growing centralization and corporatization of the railroad business in Gilded Age America.

The demise of the American Railway Union (ARU) in the aftermath of the Pullman Strike in 1894 convinced Debs of the inadequacy of unionization as a response to business concentration. While in jail for violating a federal injunction, Debs began reading texts advancing socialist ideas. Upon his release, Debs pushed the remnants of the ARU to join with others to create a new political party advocating for socialist policies. Debs’s prominence as a labor activist made him a natural choice as their presidential candidate in 1900, a task he accepted reluctantly but threw himself into with determination. Salvatore devotes as much attention to history of the Socialist Party during this period as he does to Debs himself, detailing the infighting that shaped its development. As he had as a labor leader Debs stayed clear of factional disputes, preserving his appeal within the fractious party but at the cost of allowing the personal and ideological disagreements to fester.

Though Salvatore describes the issues that divided Socialist Party leaders, he emphasizes that these were of secondary concern to Debs. Unlike the doctrinaire approach of many of its members, Debs grounded his Socialist advocacy in the Protestant theology and republican ideology he had inculcated since his youth. By positing socialism as the path towards realizing the nation’s democratic and egalitarian ideas, he made it far more appealing to American voters than abstract theories ever could have been. Coupled with Debs’s bona fides as a labor leader and his earnest and effective style of speechmaking, he became the party’s greatest asset for advancing its vision for a better tomorrow.

Yet Debs was far from the only critic of industrial capitalism in these years. As Salvatore notes, other presidential candidates were also denouncing its excesses and offering political solutions in an effort to win voters. While each election seemed to bring the Socialist Party closer to a breakthrough, the 1912 presidential election proved a high-water mark for their fortunes. As Progressive era reforms and the outbreak of war in Europe shifted the public discourse to other matters. Debs’s criticisms of the Wilson administration eventually resulted in his arrest and conviction, while his subsequent prison term proved detrimental to his frail health. Released after President Warren Harding commuting his sentence, Debs spent his final years as a shadow of his former self, trying to navigate a fractured socialist movement that struggled for relevance in the Roaring Twenties.

By situating Debs’s life within the context of the developing capitalist economy, Salvatore conveys insightfully the factors in his subject’s own transformation from a respected trade unionist and promising Democratic politician into the leading Socialist figure of his age. As a result, Debs goes from being a marginal political figure in the nation’s history to one at the heart of the choices faced by millions of Americans as values and social structures evolved in response to industrialism and the changes it brought. It makes for a book that is an absolute must-read for anyone interested in learning about Debs, and one that is unlikely ever to be surpassed as a study of his life and times.

2

2

My next BookLikes alternative

So after I read this article I decided to give MyStoryGraph a try. I can't help but mourn the opportunity BookLikes has squandered.

2

2

The end of the Irish old order

At the start of the 1870s, the great landed families of Ireland sat prosperous and sovereign in their communities. A half-century later, however, theirs was a class in terminal decline, suffering from the effects of a succession of economic and political blows. In this book Terence Dooley charts the course of the fall of the Irish landed elite, detailing the steps in their collapse and analyzing the factors behind it. As he explains, there was no one circumstance or event behind it but instead a series of developments – some global, others local – which brought an end to the social class which had dominated life in Ireland for centuries.

Dooley begins by detailing “big house” life in high Victorian Ireland. Flourishing amidst the economic prosperity of the period, numerous families flaunted their wealth by refurbishing their homes and loading them with art and other acquisitions purchased from the continent, which they often financed through loans and mortgages. Few anticipated that the good times might come to an end, leaving them unprepared when the agricultural economy went into decline in the late 1870s. With indebtedness growing, many landowners sought to maintain their income by raising the rents they charged to tenant farmers. Unable to pay the higher rents the tenants went on strike instead, further crippling landowner finances and exacerbating their financial woes.

In response to the political pressure imposed by the poorer and more numerous tenant farmers, Parliament passed a series of acts designed to facilitate the transfer of the land from the large landowners to the tenant farmers. This initiated a process of land transference that accelerated in the early twentieth century with further increases in the financial incentives for landowners to sell. By then many landowners desperate for money had already curtailed their expenditures and sold off valuable furnishings in the hope of stabilizing their situation or at least delaying their decline.

Instead, their decline accelerated with the outbreak of war in 1914. Dooley describes the blows suffered by many families with the loss of sons and husbands who fell in battle. These individual setbacks were soon compounded by the newly-empowered independence movement, which by 1920 was waging war against the British state. The big houses were prime targets for the Irish Republican Army, both as sources of firearms and as hated symbols of British occupation. Many of the houses themselves were burned down to drive out the pro-Union landowners and to prevent the buildings from becoming barracks for British forces. By the end of the Irish Civil War in 1923 the landowning class thus found themselves gutted and friendless, without even a semblance of their former status and power in Irish society.

In many respects the story Dooley tells echoes that of David Cannadine’s seminal work The Decline and Fall of the British Aristocracy. Like Cannadine, Dooley explains the various forces squeezing the Irish aristocracy as a class, to which he adds the unique circumstances facing them because of Irish nationalist politics. While their British counterparts suffered from the same economic crisis, they were spared the political assaults of the Land War and the independence movement that delivered the fatal blows that wiped them out for good. It’s an important aspect of Irish history that Dooley recounts well, making his book an important account of the transformations taking place in Irish society in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

2

2

Reading progress update: I've read 112 out of 336 pages.

This is another TBR book that I'm going to return to my shelf when I'm done with it, as it's proving a lot more comprehensive than I thought it would be.

2

2

The general who built an army

As the fifteenth Chief of Staff of the United States Army, George Catlett Marshall oversaw the transformation of the United States Army from a modest constabulary into an organization capable of waging war on a truly global scale. Though such a metamorphosis was due to the efforts of thousands of people working over the course of many years, as Forrest Pogue demonstrates in the second volume of his biography of the general and statesman Marshall’s contribution was key to the development of the Army into a force that would play a vital role in defeating the Axis powers and establishing the United states as a global superpower.

This was no small achievement, nor was it an easy one. As Pogue notes, Marshall would regard his two years of service as Chief of Staff as the most difficult of his tenure, far more so than the four years he spent in the post during the war itself. Much of this had to do with the dimensions of the task before him. When Marshall took up the post in September 1939, the Army was both under-funded and under-strength, limited by postwar disillusionment and financial constraints. Nor did the outbreak of war in Europe suddenly change everyone’s thinking. As late as April 1940, members of Congress questioned the need to expand the ground forces, believing that the low-intensity “phony war” that developed after the fall of Poland was easily avoidable. Only after their invasion of Denmark and Norway made German intentions clear did Congressional opposition to spending for a larger force finally evaporate.

Yet Marshall gained his money at the expense of time. In short order he was expected to develop a fighting force capable of deterring or defeating any German threat. Nor did the now-expanded budget solve the Army’s problems, as Marshall had to cope with the competing need to support the British in their ongoing war against Germany for weapons production. Even more problematic was the widespread reluctance of many Americans to serve in the rapidly-expanding Army for one moment longer than they were required to by the draft, a sentiment to which many powerful politicians were sensitive. So how did Marshall surmount these challenges?

Pogue makes it clear that foremost among Marshall’s attributes was a Herculean work ethic, as he dedicated nearly every day to the duties of his office. To the task he also brought considerable diplomatic skill and a sensitivity to the limits of what was possible, enabling him to navigate skillfully the formidable politics that were part of his job. Finally, there was his eye for talent, as he had an extraordinary ability to identify men of ability and a determination to place them in the posts where they could make the best use of their skills. Often this meant promoting them over older men of longer service, many of whom Marshall knew personally. That Marshall was willing to turn friends into enemies in order to prepare the Army for what lay ahead is perhaps the best evidence of his determination to succeed in his mission.

These efforts, though, were outpaced by events. Pogue spends a considerable amount of space detailing Marshall’s role in the events leading up to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, with the goal of rebutting the claims that he was part of a conspiracy to bring the United States into the war. Nevertheless, Pogue acknowledges the limits of Marshall’s conceptualization of the Japanese threat, noting that he overestimated the Army’s Hawai’ian defenses and underestimated the ability of the Japanese to attack him. The months that followed were especially tragic, as Marshall watched with despair as the Army units stationed in the Philippines were defeated by the Japanese. Yet this did not deflect him from his commitment to the “Germany first” focus adopted before the war, as he worked strenuously to launch a second front in France as early as 1942. Though Marshall was frustrated in this by the British (whom, as Pogue notes, would have borne the brunt of such an early effort), by the end of America’s first year of the war he could look with hope to the victories he knew would soon come.

Benefiting from interviews with Marshall and his contemporaries as well as considerable archival research, Pogue’s book serves as an effective monument to his subject and his achievements as Chief of Staff. Though focused on detail, it provides more analysis of its subject than Pogue’s previous volume, Education of a General, which helps to explain Marshall’s motivations and the thinking underlying them. While further analysis would have made for an even better book, given Pogue’s proximity to many of the key figures he describes he may have felt a little too constrained to offer the sort of judgments the facts he describes seem to demand, Nonetheless, his book is a valuable resource on both Marshall and his achievements, one that will likely remain required reading on the general for many years to come.

3

3

From novelty to ubiquity

Given its ubiquity today, it can be difficult to appreciate how revolutionary the bicycle was when it was developed in the 19th century. In an era when most people were dependent upon walking to get to where they were going, the bicycle gave people greater individual mobility than had even been possible without a horse. Thanks to its low cost and the empowerment it offered, it took less than a generation for bicycles to go from a faddish novelty to a mode of transportation commonplace on the streets of cities throughout the Western world.

The introduction of the bicycle took place at a time when mass media covered new developments in almost obsessive detail. Brian Griffin drew upon this abundant record to delineate the early history of cycling in Ireland from the introduction of the first velocipede to the widespread adoption of the safety bicycle. It's an impressively detailed work that identifies by name the first bicyclists, traces the establishment of clubs and some of their key members, and describes society's evolving reaction to bicycles as their riders carved out a place for themselves on the roads and in daily life. This he sees not just in their employment by the hobbyist and the well-to-do, but their use by constables, civil servants, and priests in the performance of their daily duties. As Griffin makes clear, by the end of the century the bicycle enjoyed a prominent place in both practical activities and in the recreational life of the Irish.

Griffin's meticulous coverage of the bicycle's emergence in Ireland is a great strength of the book, as he captures within these details how people came to terms with the new technology of personal transport. He leavens this with humorous stories and a generous supply of details that capture the sometimes freakish novelty and occasional frustration with which people reacted to the bicycle. Yet Griffin rarely strays beyond the specifics to consider more generally the impact of cycling upon Ireland, such as in how it affected social mores or people's sense of time and space. It's an unfortunate gap in what is otherwise an interesting and even amusing study of the emergence of cycling in 19th century Ireland, one that should be read by anyone with a passing interest in either the subject or the era.

3

3

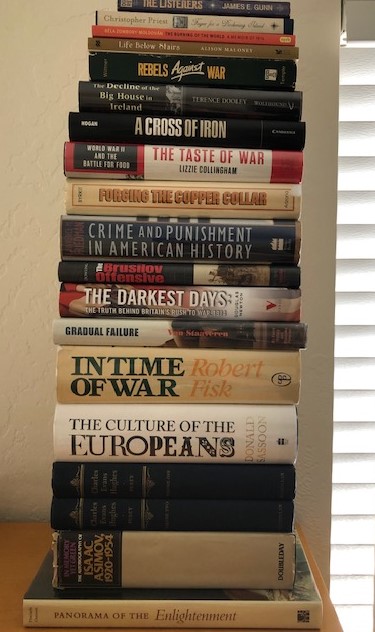

Reconsidering my TBR stack

As some of you may recall, at the start of our lovely pandemic I created a TBR stack to tackle while we were in lockdown. The idea was that a visible pile of what I wanted to clear off of my shelves would be a great reminder should I ever need inspiration for how to while away the hours.

Since then I have read over a dozen books from the stack, which I then either added to my book box or occasionally decided to retain. At this point, it isn't unreasonable to expect that my stack has been whittled down to a small pile. Yet today it has more books on it than it did when I started it:

In retrospect I realize I made an error in how I managed the pile. Instead of confining it to the books I collected initially to comprise it I kept adding to it new titles that I wanted to clear from my shelves. The problem now is that even as I'm aware of all of the progress I've made in paring down my TBR titles I feel as though I've made zero headway in getting through them. It's a frustrating and depressing feeling after months of effort.

So now I'm done adding books to it. I've already winnowed out a couple that I've accepted I was never going to be able to summon the interest to read or re-read, and now the challenge is to reread what I have there. If I can remain true to my intention, I should be able to eliminate the stack by the end of the year

4

4

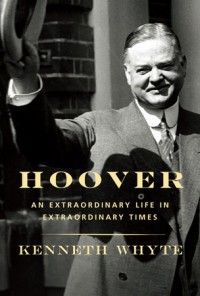

The enigma of Herbert Hoover

If American voters in 1928 believed that over the next four years they would face an unprecedented economic collapse that would cause enormous social misery, it’s likely that they would have concluded that the man they most needed in the White House was the very person they elected to it. Over the previous decade and a half Herbert Hoover had earned a global reputation as a problem-solving benefactor who had aided Americans stranded in Europe during the First World War, supported Belgians impoverished by German occupation, and provided famine relief for millions in the chaotic postwar environment. His administrative genius was further demonstrated over the course of his eight years of service as Secretary of Commerce in the presidential administrations of Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge, during which he regulated the new marketplaces created by technology, championed product standardization, and oversaw disaster relief in the Mississippi Valley basin. Yet four years later Hoover would be turned out of office in a landslide even greater than the one he enjoyed when he was voted into it, a damming judgment of his response to the Great Depression.

Herein lies the great enigma of Hoover’s presidency: how is it that such an accomplished humanitarian and administrator could have fallen so short in his response to the Great Depression? It is the question that hangs over any assessment of his career, one that is even more challenging to address given its length and his multifarious achievements. Kenneth Whyte rises to the challenge with a book that encapsulates the range of Hoover’s life and draws from it a sense of his character. A longtime editor and a biographer of the newspaper mogul William Randolph Hearst, Whyte employs a discerning eye and an adroit pen to the task of drawing out Hoover’s personality and assessing his achievements.

The first of these achievements was Hoover’s rise from adversity. The son of Iowa Quakers, Hoover was orphaned at an early age and forced to live with various relatives. Thought he did not distinguish himself academically his work ethic was evident at an early age, and through his diligent labors he won admission to the newly-created Stanford University. After graduating with a degree in geology, Hoover embarked on an incredibly successful career as a mining engineer. Whyte’s chapters on this part of Hoover’s life are among the best in the book, as he details the brusque management style and oftentimes shady business practices Hoover employed to make a considerable fortune at a young age.

Seeking new challenges, Hoover was preparing to move from London back to California when the outbreak of war in 1914 changed his life dramatically. Boldly stepping up, Hoover soon emerged as a dominant force in humanitarian relief thanks to his managerial skills and his numerous contacts. When the United States entered the war, Hoover was a logical choice to head the food production effort, and by the end of the conflict he had cemented his reputation as a “can-do” figure. Though nominally a Republican, Whyte sees Hoover’s association with the values of Progressivism as far more relevant to understanding him, which he identifies in both Hoover’s approach to his roles as Commerce secretary and as president.

It is in how Hoover viewed his role as president that Whyte finds the source of the problems that bedeviled him. As an apostle of scientific management, Hoover had little experience with or respect for the political game. This attitude proved self-defeating in his dealings with Congress, as his poor relations with them frustrated his ability to achieve the measures he sought. This also led him initially to underestimate Franklin Roosevelt, who with the help of a Democratic Party effort to associate Hoover indelibly with the Depression defeated Hoover when he ran for reelection. Embittered by Roosevelt’s attacks on his record, Hoover spent the remaining thirty-two years of his life in search of redemption, both through championing a new version of American conservatism and by gradually regaining respect for his administrative expertise through his work on a series of commissions.

In writing this book Whyte masters two enormously difficult challenges: encapsulating Hoover’s extensive life within a single volume while simultaneously providing a convincing interpretation of his withdrawn personality. From it emerges a portrait of a gifted and driven individual who succeeded in every field to which he applied himself except the one least suited for his disposition. Where the book suffers is in Whyte’s treatment of the Depression, which he interprets through a monetarist lens; while this highlights several often underappreciated aspects of the crisis, it comes at the cost of glossing over both the miseries people suffered and how they – rather than Hoover’s often contradictory monetary policies – served as the basis for the public’s judgment of Hoover’s failure. This mars what is otherwise an impressive achievement, one that currently stands as the best encapsulation of a complicated man within the confines of a single volume.

1

1

The master of Britain's manpower

Of the many editorial cartoons drawn by David Low during the Second World War, perhaps the most famous was the one he penned in May 1940 after Winston Churchill formed the coalition government that he would lead as prime minister. Entitled “All Behind You, Winston,” it depicts Churchill at the phalanx of a group of determined men, all of whom are rolling up their sleeves in preparation for the fight ahead. Standing next to the prime minister is Clement Attlee, the leader of the Labour Party and a natural choice that reflected the politically united nature of the coalition. On Attlee’s other side, however, is another large figure, one who almost seems to be crowding past Attlee to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with Churchill. That figure is Ernest Bevin.

On the face of it, Bevin’s inclusion in the front rank is a curious one, as Bevin had just been named minister to what was regarded as a second-rank department and who would not even win a seat in the House of Commons for another month. Yet Alan Bullock makes it clear in his second volume about Bevin’s life and times that such a position was more than warranted, as in his role as Minister of Labour and National Service Bevin played an utterly indispensable role in addressing one of the greatest challenged Britain faced in the war: the mobilization of the nation’s manpower for the drawn-out struggle against the Axis powers.

To have been charged with this responsibility in the coalition government was both unusual and completely understandable. Given that Bevin had never even served in Parliament before, his sudden promotion to ministerial office was nothing short of extraordinary. As the longtime head of the Transport and General Workers’ Union (TGWU), however, Bevin was an ideal choice for the post, especially after the years of poor relations between the labor movement and the British state. Bevin brought instant credibility to his new post, as well as enormous energy and a wealth of new ideas.

First among them was the need to strengthen his position. From the start Bevin insisted on centralizing within his ministry authority over the nation’s manpower. Though he would never gain total control, Bullock shows how Bevin won this fight in the Cabinet. This put him in a prime position to address the competing challenges facing the allocation of manpower from an early stage. Here the core problem was in resolving the competing demands of industry and the military, which often complicated the government’s efforts to run as efficient a system as possible. Bullock’s coverage of this throughout the book illustrates that this was a challenge that was never fully resolved, and could only be managed to the best of his ability. Added to this was Bevin’s reluctance to impose coercion, as he believed firmly that such efforts reduced workers’ efficiency rather than aided it.

Bevin’s views about doing what was best for the worker were a hallmark of how he approached labor problems throughout his time in office. With a career spent fighting alongside as well as for workers, Bevin based all of his positions on his appreciation for their qualities and his assumption of their commitment to the nation’s wartime goals. His efforts to improve conditions for workers earned him considerable goodwill, making it easier (though far from easy) to work out the numerous compromises necessary for maintaining the war effort. Second only to this, though, was Bevin’s interest in ensuring that the British worker was fighting for a better future, and as the immediate crisis ebbed he spent an increasing amount of time concerned with the issues of postwar reconstruction. It was a testament to his stature as a minister that as the coalition came to an end he was approached about succeeding Attlee as the party’s leader – an offer that Bevin firmly declined.

Bullock’s book is so much more than an account of Bevin’s tenure as Minister of Labour. It also describes Bevin’s transition from labor to parliamentary politics, as well as his growing involvement in questions of foreign policy. Though dense with details of wartime initiatives and parliamentary battles, Bullock provides wonderfully clear descriptions of Bevin’s policies and how they worked within the context of the war effort. It makes for a magnificent work that can be read with profit not just by those interested in Bevin’s life or his contributions to the war as Minister of Labour, but by anyone who wants to understand the inner workings of Churchill’s wartime government.

4

4

How I amuse myself

This morning I came across an ad for an opening in the Regius Professorship of Greek at the University of Cambridge. Not having anything better to do, I decided to submit my cat's application for the position.

Her insistence on being flown first class for any face-to-face interview may be a deal-breaker.

The political career of a liberal lion

Among the quotes printed today in American passports is one that reads: “It is immigrants who brought this land the skills of their hands and brains, to make of it a beacon of opportunity and hope for all men.” For Herbert Lehman, the man who spoke those words, this was more than just political rhetoric. As Duane Tananbaum makes clear in his deeply researched account of Lehman’s political career, it was one of the many sincerely held views that he fought for strenuously, even in the face of what often proved insurmountable opposition.

As the son of an immigrant Lehman knew well what it meant to be one. The son of a businessman and commodities trader, Lehman grew up in a well-to-do family. As a young man he enjoyed success as a textile manufacturer and investment banker, yet in his spare time he volunteered at a settlement house on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. It was here where he first met Lilian Wald, with whom he enjoyed a lifelong friendship. Tananbaum’s focus on Lehman’s partnership with Wald illustrates his approach in the book, which is to frame Lehman’s political career in terms of his relationships with the major figures with whom he worked. In this respect, Wald was the first of many with whom Lehman labored to address the social ills of his era.

Another was Al Smith. Though the two men came from very different backgrounds, they shared a belief that the government should use its authority to address society’s problems. Throughout the 1920s Lehman played a number of important roles in Smith’s political operation, spearheading his campaigns for governor and working for his selection as the Democratic Party’s nominee as president in 1928. Seeking to maximize the turnout of Jewish voters in New York City, Smith encouraged Lehman to run for lieutenant governor that year; though Smith lost New York in the Republican route that year, Lehman’s victory inaugurated a new career as an elected official, one that would engage Lehman for the next three decades.

As lieutenant governor, Lehman served under Smith’s successor, Franklin Delano Roosevelt. This began a firm partnership that lasted until Roosevelt’s death in 1945. When Roosevelt was nominated for president in 1932, he encouraged Lehman to run to succeed him, believing as did Smith that Lehman’s presence on the ballot would help with Jewish turnout in the state. Lehman went on to serve as governor of New York for a decade, during which time he worked to emulate Roosevelt’s New Deal programs. In this he was frequently stymied by a Republican-controlled statue legislature, which may have contributed to his frustration with his post. Though Lehman aspired to a seat in the United States Senate and frequently announced his intention not to run for another term, his proven vote-getting abilities (which Tananbaum attributes to Lehman’s demonstrable sincerity and liberal politics rather than to any great oratorical or other political gifts) made him indispensable to Democrats, who pressured him constantly to run again.

Lehman’s tenure as governor coincided with the rise of the Nazi regime in Germany. The governor was not shy about using his position as the most prominent Jewish elected official in America to lobby for Jewish causes, notably the admission of Jewish refugees. As war threatened, though, Lehman longed to do more, and in 1942 he joined the Roosevelt administration as the director of foreign aid operations, first within the State Department and then as the first director of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. Lehman struggled throughout the war to ensure that his agency was not slighted in the battle for resources, a struggle that grew more difficult when his friend Roosevelt was succeeded by Harry Truman in 1945. Frustrated by the declining priority of aid in penurious postwar budgets, Lehman resigned from his post in 1946.

No longer in office, Lehman nonetheless remained active in politics. When Robert F. Wagner resigned in 1949, Lehman finally achieved his long-cherished goal of becoming a United States Senator. Lehman’s seven years in the Senate take up nearly a third of Tananbaum’s book, as he details his subject’s often frustrating battles on behalf of liberal causes. Though he emerged early on as a prominent opponent of Joseph McCarthy, Lehman’s greatest foes in the Senate were the conservative Southerners of his own party. Benefiting from their greater seniority, these senators used their positions as committee chairs to bottle up the reform measures Lehman fought for, such as civil rights legislation and measures to ease immigration restrictions. Tananbaum is blunt in his assessment of Lehman’s unwillingness to play by the rules of the Senate’s club, a decision which limited his effectiveness as a legislator but established him as the liberal lion of the Senate by the time he retired from public office in 1957.

Tananbaum notes that by the time of Lehman’s death in 1963, Congress was on the cusp of passing many of the measures he had championed. While he may be overly generous in crediting Lehman for his role in making it possible, Tananbaum nevertheless does an excellent job of recounting the political career of one of the great champions of New Deal liberalism. While his focus on Lehman’s political career to the exclusion of his personal life and business career is regrettable, his book represents a remarkable labor of research and analysis. It’s a fitting monument to a great and often underappreciated man, one that should be read by anyone interested in Lehman and his achievements.

1

1

Taking the plunge on Herbert Hoover

One of the things that I find the most frustrating about the pandemic is how it's cut off my access to inter-library loan. Losing the ability to request otherwise inaccessible books has put a crimp in my plans for my website, as well as denying me the ability to evaluate books before spending the money to add them to my shelves.

Worst of all, though, has been how it's supercharged my acquisitiveness. For a while now I've tried to rein in my book buying by reminding myself that with a little planning and a little patience I can read just about any book I want without having to spend a cent. Thanks to this, I have kept my bookshelves in a more manageable state than they would be had I purchased every book that I wanted to read. My TBR pile would be enormous.

For the past several months, though, inter-library loans have no longer been a option. My book buying has gone up commensurately. While I've focused on making long-term acquisitions, there have been a few that have ended up in the shopping cart less because I wanted to keep them then simply because I wanted to have access to them.

The latest candidate for acquisition is the six-volume Life of Herbert Hoover. It's a series that I've orbited around reading for nearly three decades now. At one point I owned the first three volumes, only to jettison them as low-priority reads cluttering my shelf in place of more useful books. Because, if I wanted to read them I could just request them through ILL, right?

Now I'm thinking about how much I'd like to have them. It helps that I'm in the process now of clearing out the space on my shelf for them by reading Forrest Pogue's four volumes on George Marshall, which I'm enjoying but would probably never reread. Reading about Hoover will probably prove even more time-consuming, but he's someone who I've always wanted to understand in depth. Six books covering his life would certainly achieve that; the challenge is to keep the cost manageable.

2

2

On to William the Conqueror!

My latest post is up on my Best British Biographies website! As I'm moving on to the Normans, I wanted to detail some of the changes to my approach going forward, as I won't have the luxury (or interest, for that matter) of reading every biography of an English monarch gong forward.

And given the out-migration from Booklikes, this seems an excellent point to ask that when you click on the link to take the opportunity to bookmark my site as well. As loath as I am to admit it, at the rate things are going we may not have a platform here to meet for much longer.

A Cold War thriller devoid of thrills

When I was growing up, my local library was one of my favorite haunts. It was by walking through their stacks and perusing their displays that I came across many of the books that I would take home to enjoy. One of these was Charles D. Taylor’s novel. Before Tom Clancy made his millions churning out tales of Cold War-era conflicts between the superpowers, Taylor published his tale about a battle between American and Soviet armadas in the Indian Ocean. I can still remember how I was drawn to the stark minimalism of the dustjacket, and how eagerly I devoured the description of the battles that waged between the opposing vessels. Recently I encountered a paperback copy of the book at a used bookstore, and seeing the book again brought all those memories of reading it flooding back, inspiring me to reread it to see how well it well it has held up.

What stands out most today are the very elements I avoided when I first read it. More interested in the naval battle than I was in the characters, I skipped over Taylor’s development of the novel’s two central figures. Though commanding forces on opposing sides, the two men, David Charles and Alex Kupinsky, are both portrayed as honorable men who over the course of their careers develop a strong friendship towards one another. Taylor first matches them up against each other during the Cuban Missile Crisis, when the two young lieutenants find themselves on ships facing off against one another in the blockade. They meet face-to-face over a decade later while stationed as naval attaches in London, by which time they have gone on to further distinction in their respective careers.

All of this is meant to add a layer of tragedy to the battle that the author situates at the heart of his novel. Yet for all of his effort Taylor fails to develop his two main characters beyond this. Instead they become little more than archetypes of great naval officers – smart, dedicated, brave, and patriotic leaders of men. Even the log entries and letters that Taylor inserts between the chapters don’t do a lot to differentiate them or flesh them out beyond the roles they perform. And these two represent Taylor’s most sustained effort to develop any of the characters in his book, as the rest are often little more than names or even just titles inserted to play supporting roles.

This matters when it comes to the action. It was here where the contrast with someone like Tom Clancy stood out for me; by developing his characters to the degree that he does, Clancy used them effectively to convey the emotional impact of the action in his books. By contrast, the action in Taylor’s novel comes across more as zapping targets in a video game, with little real emotional impact conveyed in the description of the thousands of men dying as a result of the battle. It all feels incredibly hollow and pointless, an excuse for writing up what amounts to a paper exercise hypothesizing what a 1980s naval battle might look like. The artificiality of the premise and the conditions only underscores this, as it’s all so Taylor can have his ships pounding each other to smithereens.

In retrospect, its easy to see why novels such as Taylor’s are not regarded as great literature. For all of the enthusiasm their authors bring to writing them, by prioritizing the action over the characters they leave out what it takes to make for truly gripping fiction. The result is little more than a series of descriptions of imagined battles that in this book are conveyed with all the enthusiasm and punch of the rattling off of a list of ships’ names in a column. It makes me realize just how much my appreciation of the book is tied up with nostalgia for my naïve youth, and how in the end this caused me to remember this book with more fondness than it deserves for its merits.

4

4

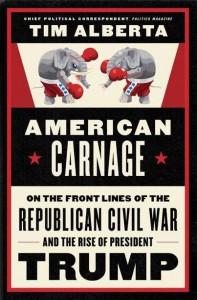

An "inside the Beltway" account of a party in crisis

Though the title is taken from Donald Trump’s 2017 inaugural address, this book is about more than just the 45th president of the United States and his impact on the Republican Party. Instead what Tim Alberta provides is a Washington-eye view of the evolution of the national GOP from the 2008 election to the midway point of Trump’s presidency. A longtime political reporter, Alberta draws upon a wealth of interviews with many of the key Republicans in Congress, featuring them as they key figures in their party’s evolution from the pro-immigration supporters of free trade and fiscal restraint into the more nativist, protectionist, and xenophobic party they have become since 2016.

As Alberta demonstrates, the factors that led to this transformation were present well before Trump announced his candidacy for the presidency. By the end of George W. Bush’s presidency Congressional Republicans faced a lot of internal discontent with their deficit spending habits and the costs of two interminable wars in the Middle East, to which was added the onset of a severe recession. With Barack Obama’s victory over John McCain in 2008, Republican leaders feared they might be politically marginalized for the next generation. Even in the afterglow of Obama’s victory, though, his team recognized that they would likely face a backlash because of the dismal economic conditions and the hard choices before them.

That backlash was the Tea Party movement. Its energy translated into Republican victories up and down the ballot in the midterm election. Yet even as Republicans benefited electorally from public dissatisfaction with Obama’s administration, Alberta notes the emerging tension between the party leadership and the new members of the caucus, many of whom rode to victory on the basis of this dissatisfaction. The new House Speaker, John Boehner, bore the brunt of this conflict, as the more radicalized members of his majority often pressed for actions that Boehner (who at one time was considered on the extreme wing of the House Republican caucus) resisted as pointless. Such extremism proved counter-productive in the Senate races that year, as Alberta notes how the selection of the more radical candidates cost the Republicans winnable races that would have given them unified control of Congress.

This tension only grew over the next six years, inspiring ambitious Republicans and frustrating legislative achievements. With Obama’s reelection victory in 2012, many within the party worried that they were on an electorally unsustainable course that would prove disastrous. Three years later the Republicans had a primary field notable for its considerable diversity, yet in the end what the base desired most was not ideological extremism or detailed conservative proposals, but someone who tapped into their cultural anxieties. Enter Donald Trump, whose often outrageous rhetoric and media savvy combined to win the nomination over a number of prominent party figures. Though many Republican officeholders blanched at his statements, his unexpected victory cuffed them to a mercurial figure who demanded total loyalty and who was even willing to sacrifice political power to get it.

Drawing as he does from conversations with many of the key individuals involved, Alberta offers an insider’s account of a decade’s worth of American politics. As perceptive of much of his analysis is, though, Alberta’s book suffers from some unfortunate limitations. These are a consequence of his “inside the Beltway” focus, with little consideration of developments at the state and the local level. With only a marginal effort made to unpack the dynamics that often drove many of the events he describes, the Congressional maneuvering and political infighting he describes can assume a greater importance than it might otherwise possess. A more expansive coverage might have made for a stronger book, albeit perhaps a less readable one. For with its mixture of reporting and retrospective commentary, Alberta’s book serves as a compulsively readable record of an important moment in the history of the Republican Party, one the consequences of which continue to ripple outward.

3

3